Wednesday, March 31, 2004

The Attack of the Brood X

Called periodical cicadas, the thumb-sized insects emerge every 17 years and fly around in a noisy, mating frenzy before dying weeks later, littering the area with crunchy shells.

More here.

Mistakenly called locusts by early settlers, they are distinguished by their beady red eyes. What is most memorable is the deafening noise the males make with drum-like organs called timbals to attract more sedate females.

- Reuters Wire

(!)

posted 12:22 AM | 1 comments

Tuesday, March 30, 2004

Disappearing Nader

The thought just occurred to me, in a split-second of bad judgement, that a movie could be made about the Democratic Party arranging for the "accidental" death of Ralph Nader. It would be a great Machiavellian conspiracy, complete with "autonomous" special-interest organizations and corporations acting "independently" out of a network of double-doored dumpsters parked behind nondescript cheap Mexican restaurants.

The story would be bust wide open by a hottt college journalism junior (with a cute nose and large breasts) interning at the Seattle Post Intelligencer the fall of the election, someone who looks so innocent and naive that she manages to trap the crooks, Columbo-style, into giving up the goods in otherwise unsuspecting encounters. Her life is put in danger by a squad of vindictive Greenpeace-supporting squirrels (allied with the Democrats out of frustration with the Green Party's impotence) who attempt to pummel her to death with a particularly large winter stash of pointy acorns. In the climax, the poor girl is held hostage by Al Gore, who straps her to an uncomfortable wooden schoolchair for two hours at the University of Washington in order to lecture her on Global Warming, the Internet, and Mexican Peanut-Butter production subsidies.

There's the usual complement of running frantically away from exploding things, sinister cloak-and-dagger encounters in seedy parking basements, and well-orchestrated break-ins into wiretapped party headquarters to -- um -- hook up better microphones in the bathrooms. And raid their executive wetbar, which contains the last remaining bottle of '67 Vieux de Telegraph Chateauneuf du Pape (which they drink back in the newsroom only to find that it's turned to red vinegar during its cellaring).

Of course, the plot twists like a cheap pretzel, folding in on itself with no apparent order. First it all seems like a straightforward conspiracy (got that?). Then it looks like she's being conned into believing the conspiracy so as to distract her from a sinister Republican Plot to recycle radioactive Bubble-Yum from nuclear submarines into park benches. Then, another clue reaffirms her belief in the conspiracy. Then it looks like the Green Party is in on it as well (motive: Nader's crippling halitosis), before the protagonist's really, really, really chubby cat -- a half-blind tabby named Oscar -- brings the crime crashing down -- literally -- with a single leap from a fourth-story window and the casual swipe of his paw.

The whole thing has as its backdrop a love interest -- a shaggy-haired entertainment editor from the UW student paper whom the protagonist's been dating. The affair turns at right angles to the conspiracy plot, creating a kind of tight entertainment double helix! (Whatever that means.) This boyfriend of hers is a guy who, at first, seems innocent, then looks as if he might be a spy, then acts altruistic when he nearly saves her life (from the chipmunks or squirrels or whatever), then ends in a fight when he complains that she's too preoccupied with her investigation to love him right.

Until the VERY end, of course, when she lands the scheming Dems in handcuffs and he shows up at the precinct looking fashionably, sexily unshaven with greasy unwashed hair and tells her that he always believed in her and the two go off, holding hands, to get coffee at the Sulking Pidgeon, Oscar perched on the boyfriend's back, purring contentedly.

I'll take no less than 100 million for the production of this fine script idea. Send all offers to me. Julia Roberts need not apply.

posted 9:55 PM | 0 comments

Sunday, March 28, 2004

Feeling v. Jigsaw Puzzle

Check out Stephanie Zacharek's review of Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind at Salon. I think her comments on the Kaufman/Lynch/Nolan genre of crossword/jigsaw-puzzle filmmaking are pretty close to the mark. Plus, it makes a nice follow-up to my "Little Big Idea" post. Here's the pertinent excerpt from Zacherek's review:

You might argue that this is a dramatic device, a way of breaking what would otherwise be an incredibly intense story into easily digestible bits. But I think it's symptomatic of a much larger, thornier problem in moviemaking today, one that undercuts the reasons movies have come to mean so much to us, emotionally and culturally, in the first place: The '90s were all about ironic detachment -- it was uncool to care too much about anything, or at least to admit as much. Now that we've tread somewhat tentatively into the 21st century, most of us claim to have gotten over the irony thing. And yet, many of the movies of the past five years that have been hailed as inventive and interesting by young audiences -- pictures like "Memento," "Being John Malkovich" and "Adaptation," the last two written by Kaufman -- are also movies that work hard to wow us with their jigsaw intricacies.

It's as if young filmmakers fear that their audiences will become bored with a movie if they don't have a clever mind-boggler to wrestle with along the way (the equivalent of a magnetic bingo game on a long car trip). In grappling with these perplexing riddles, we're supposedly exercising our intellect. But isn't it also possible that we're using them as a handy diversion, a way of distancing ourselves from emotions that might be too strong for us to deal with easily? Labyrinthine plots are supposed to stimulate us. But are they really just distracting us from the work at hand -- the work of feeling?

posted 4:15 AM | 0 comments

Friday, March 26, 2004

Ken Burns Interview

There's a nice, fast interview of documentarian Ken Burns on Kodak's cinematography website. Check it out.

posted 5:19 PM | 0 comments

Missing Josh

We love you, we miss you, please please come back soon, Josh.

posted 5:17 PM | 0 comments

The Little Big Idea

I think Dr. Willis McNelly at the California State Univesity at Fullerton put it best when he said that the true protagonist of a SF story or novel is an idea and not a person. If it is good SF the idea is new, it is stimulating, and probably most important of all, it sets off a chain-reaction of ramification-ideas in the mind of the reader; it so-to-speak unlocks the reader's mind so that the mind, like the author's, begins to create. Thus SF is creative and it inspires creativity, which mainstream fiction by-and-large does not do. We who read SF (I am speaking as a reader now, not a writer) read it because we love to experience this chain-reaction of ideas being set off in our minds by something we read, something with a new idea in it; hence the very best science fiction ultimately winds up being a collaboration between author and reader, in which both create -- and enjoy doing it: joy is the essential and final ingredient of science fiction, the joy of discovery of newness.

Philip K. Dick (in a letter)

May 14, 1981

As reprinted in the Preface to Vol. 1 of The Collected Stories of Philip K. Dick

So there you have it: PK Dick considers science fiction "creative" and most everything else old hat.

I don't buy it.

Here's my take on The Great SF Debate: SF is just another means by which to achieve the same ends as other genres -- the illustration of the myriad facets of human nature. SF consists of a different set of emotive and intellectual triggers, tricks and gimmicks and plot devices, than, say, Dickens or Shakespeare, but the goal of both types of literature (actually, all three types) remains the same: to reveal us to ourselves. To the extent that we as a species remain fundamentally unchanged, the stories we tell remain basically the same.

So Blade Runner may use killer robots and off-planet colonization and a long, drawn-out bounty hunt as dramatic devices to get us thinking about the human tendencies to enslave others, construct false us-versus-them dichotomies, and commit stupid reflexive acts of violence. But you don't need all the future technobabble to illustrate these demons of humanity or to trigger the question: "what does it mean to be human?"; you just need a bag of really good dramatic metaphors and speeches, I don't care from what time zone or technological age. 22nd century or 15th, what difference does it make?

Personally, I find SF generally less desirable than other genres because, by its nature, it is philosophical Art created in very, very broad strokes that tend to rudely drown out the finer points of human existence. It rigs a scenario so absolute in its technological and scientific departure from our own world as to come across as obvious gimmickry. Yeah, man versus robot literally begs the question "what does it mean to be human," but the setup seems heavy-handed in comparison to man versus implicitly-discriminated-against man. The more delicate the metaphor, the better, and SF seems set on giving us Big Metaphors through tacky and bogus setups.

Most SF is front-loaded via the silver-bullet "idea," that prize of literary construction that Mr. Dick seems to value above all else. The power of the Big Idea is that you can explain a PK Dick novella with a few lines of prose. This is why discussing SF novels makes for great coffeeshop chatter or across-the-table Hollywood pitches. Just the set-up floors you with a conundrum of some sort. The flip-side, however, is this: why do you need 2 hours of motion picture (or 150 pages of text) to get everyone on board? With most SF, I usually know what the point is before I've even turned the first page or seen the first frame; it's all downhill from the Idea.

One of Chekov's characters says in Uncle Vanya: "Ideas by themselves are nothing. It's you who should have been using them, doing real work!" Exactly. In its insistence of the idea as the pivot point of existence, Science Fiction defines itself out of a job. "What it's about" is all that SF is about and that leaves little room for how it's about it, including all the random rhythms and jangles, screw-ups, and empty spaces in which everything happens to a characer in a plain vanilla world with no Apparent Plan. I donít' know about you, but I'd much rather read a book about an off-kilter person stumbling across an idea than about an idea itself. People just make more interesting protagonists. Off-kilter is more fun.

In SF, the environment as rigged to espouse the Idea is often the whole point of the affair, the people mere pawns in the plot's chess game. More traditional drama -- the really good stuff, I think -- shows how and why people build their environments up, finding themselves trapped or liberated by them. A Chekhov play requires 2 hours and lots of subtle character development to build up to a point. And then he only arrives at epiphany not via some exploding planet or melting android, but rather through some miraculous emergence of theme from pseudo-white-noise, an idea cleverly appearing through seemingly-random conversation and happenings. To me, the Chekhovian method is more instructive as to human nature because it's all about HOW you get from "slice of life" to epiphany, not how a Grand Theorem imposes itself on a group of characters via Kafkaesque alternate reality machine.

Coming back around to the "so fucking typical" question, though... Stylistically and conceptually, you must admit that Blade Runner borrows pretty heavily from those genres before it. There's the private detective film noir genre, with the typically unscrupulous bounty-hunter Deckard (molded after Sam Spade and Philip Marlowe) on the prowl in a typically dressed-down, grittified, and gloomy Los Angeles that looks little more than an update of Taxi Driver's mid-70's Manhattan or Polanski's Chinatown. And what about Shakespeare? Doesn't the "What does it mean to be human?" question find equal soliloquy time in Shylock's "If you prick us" speech as the "I've seen things" finale to Blade Runner?

Minority Report -- that's new inninit? Uh, no. The whole theme of one man pre-judging another or just plain judging (wrongly) at all is old, old, old. The idea of Golden Boy falling prey to jealous detractors is also ancient. (Read the Bible and weep, folks). The danger of blindly following the voice of the muses is surely dealt with in more than one Greek play. And the overarching Kafkaesque atmosphere is, well, derived right out of The Trial.

If all this sounds like an overly-reductive analysis, it is. That's my point. If you're set on judging a work of art purely (or primarily) on its ideas rather than its overall effectiveness in emotively moving us, then we might as well all give up on the whole Artistic Endeavor and resign ourselves to putting on productions of Oedipus Rex and reading our leather-bound King James.

I propose, instead, as many have before me, that we judge a work based on how well it engages us emotionally and intellectually on some holistic level -- how successfully the Artist invokes dramatic and situational metaphors to present us to ourselves. The Big Idea or the Rigged Environment are only two of many factors in a very complex narrative or visual equation -- why celebrate the SF components above all else? Why make a bigger deal out of what something is about than how it is about it? The more reductive the criteria for judging a work of Art, the less interesting art ultimately becomes. So if you're gonna dog something, don't attack the Idea, attack the execution. Attack how it failed to present you to yourself, the whole point of the enterprise.

Anyway. I'll keep on watchin' film noir, be it set in Nebuchadnezzar's hanging garden or 3019. And stories about love saving people's lives. "What's New? Nothing's New. Everything's Old," groans Vanya in "Uncle Vanya" -- but each instantiation of old ideas always brings new joys and pleasures and insights. There are, after all, a lot of detailed facets to the human condition; things that are perhaps inarticulate in Big Idea speak. We could keep on writing for thousands of years and still not completely describe it. There's more to life than Big Ideas. If there wasn't, what would there be to man outside of Logic? What would we need from emotions -- those bizarre and mysterious things that strangely seem to be the whole point of everything? And what of God?

posted 1:37 AM | 0 comments

Tuesday, March 23, 2004

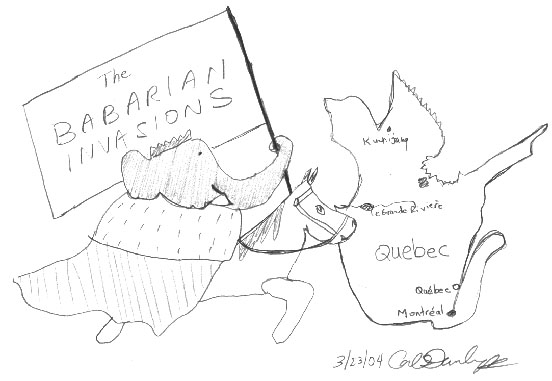

After all the Academy Award Hoopla, The French Want Canada Back!

posted 12:32 AM | 0 comments

Monday, March 22, 2004

In Defense of the So Fucking Typical

"This movie sucks! It's so fucking typical. He's all hooked on death, and she's all hooked on living...and she's going to teach him some things."

-- Kim on "Harold and Maude"

Who cares if it's "so fucking typical?" Casablanca is as fucking typical as it gets, yet it's still a great fucking movie.

"Annie Hall" is all about a guy obsessed with death and dying who falls for a midwestern girl chock-full of charm and a zest for life. A very similar state of affairs to "Harold and Maude," and yes -- a very fucking typical scenario -- but also very unconventionally portrayed. Also a great fucking movie. (This used to be my litmus test for potential girlfriends to see if they laughed in all the right places. No one has ever passed -- well there was one once, but she's taken).

I mean, we all agree that the idea of these movies is, at their most boiled-down, reduced, serve-it-in-a-teacup-with-a-biscuit form, entirely conventional and well-worn. But what isn't these days? The trick is in the executin', my dear, and "Harold and Maude" works some pretty fucking delightful magic.

I could spell out everything I really like about the picture and all the memories I have associated with it, but I'll keep it brief for the sake of everyone else. The scene where Harold and Maude are rolling around in the field of little flowers on a lazy afternoon. The tollbooth sequences with the cop. The "If you want to sing out, sing out" duet that Harold and Maude sing in maude's converted boxcar while they do a little dance.

The pure feeling of just driving, driving, driving -- all day long -- along the twisty, windy craggy roads of Northern California, where the afternoons stretch out into forever with Cat Stevens as your hitchhiking passenger, strumming on the old banjo.

Wonderful.

Watch enough movies, folks, (or read enough books or see enough plays) and you'll figure out that there are no new stories to tell. The Greeks beat us to it a long, long time ago (even if only 7 out of Sophicles' 123 original manuscripts survived the Burning of the Great Library at Alexandria) and we've been merely polishing the dramatic stone of the same basic forms and themes ever since. As a playwright/screenwriter, I have to resign myself to simply telling the same old stories -- the ones that are "so fucking typical" -- in a fresh way that rings true. That's it. I can't do anything else. Neither can Charlie Kaufman or Chris Nolan or David Lynch or any of the other Kings of Gimmick currently working in Hollywood these days. All the backwards-time hand-waving and pretzel-twisting of the plot cannot hide this basic truism of drama: it's all been done, folks.

As a viewer, you have to overcome this (at first) crippling, depressing notion. You have to -- like Maude admonishes Harold in that field-of-flowers sequence and as American Beauty demands in its tagline -- look closer. Then, resolved in the tiny, little details, the genie emerges. And oh, what an amazing fucking species we must be to create such exquisite nuance! What a marvelous thing to behold a book with an excellent turn of phrase or a motion picture with emotional truth right there, staring at you, right in the fucking face with nothing between you and the experience.

Yeah, they're all old stories, all So Fucking Typical. But beautifully fucking illustrated. (Apologies to "Trainspotting").

Rock on, Harold and Maude, Alvie and Annie. After thirty years, give or take, you still blow me away.

posted 11:32 PM | 0 comments

Monday, March 08, 2004

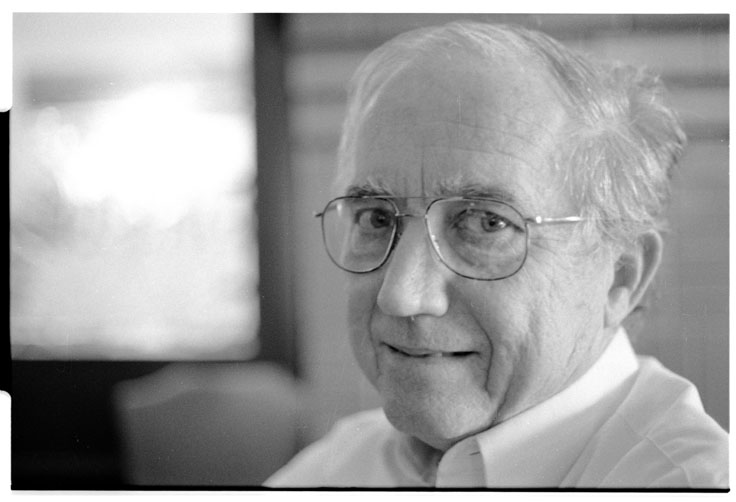

Awesome Dad

I was at my dad's office on campus over winter break and, while perusing his bookshelves, picked up a 60's-era text on set theory lingering from his old PhD Math days (we're talking around the time of the controversial Robert Lee Moore ousting, when UT-Math was in the final throes of applied mathematics under its then-chair William T. Guy and poised on the threshold of Pure Math, of which my dad was an aspiring practitioner). As I lounged in a chair, flipping through the book, my dad sat at his PC, working, I believe, on some atmospheric chemistry simulation. It was a nice father-son moment, I thought, and suddenly looked up mid-book to ask what the hell a "ring" was.

Without much deliberation at all, my dad got up from his chair, walked over to his wall-length chalkboard, erased a small portion of real estate, and then outlined the basic principles and features of set-theoretical rings. It was kinda cool, this automatic, impromptu lecture; and even though I didn't really grasp all of it, I felt a sudden deep love and appreciation for my father. It was really something.

Anyway, after he was done a few minutes later (I think he saw my eyes glazing over a bit), my dad quietly put the chalk down, slowly rubbed his hands against one another, and, without looking up, just said humbly "I haven't thought about that stuff in over 35 years. God."

The room was dead silent. We both teetered on the verge of losing it, each in our own way: my dad, likely wondering about the life he gave up on when he abandoned Set Theory for the young, growing field of environmental engineering; and myself, thinking how amazingly three-dimensionally brilliant my dad is.

Wow.

posted 1:27 AM | 1 comments