Friday, March 29, 2002

Crimes and Misdemeanors: On Existential Terror and Morality Lost

"Well, I'm not a saint, okay!"

"But you're too easy on yourself. Don't you see that that's your problem: you rationalize everything; you're not honest with yourself. What are future generations going to say about us? Some day we're going to be like him [motions towards skeleton] - this is what happens to us. It's very important to have some kind of personal integrity. I'll be hanging in a classroom some day and I want to make sure that when I've thinned out, I'm well thought of."

The quote is actually from Manhattan, a film Woody Allen made in 1979, ten years before Crimes and Misdemeanors. But it neatly captures the thematic core of this later movie, a story about trying to get one's moral bearings in a universe where good people suffer and criminals prosper. To an extent, this theme runs throughout all of Allen's work because it is the philosophical dilemma haunting the Jewish Nebbish, a character around which Allen centers every one of his films. Usually these nebbish characters mourn their diligent failures in the face of others' phony successes: a serious comedian struggling with his coke-snorting, audience-deadening producers (Manhattan) or an insecure writer losing a girl to a slick rock musician (Annie Hall). But, in Crimes and Misdemeanors, Allen ups the ante of evil to the high stakes of murder. And instead of suffering unemployment or loneliness, the most moral character in the film - a Jewish rabbi - gradually goes blind.

In this way, Crimes and Misdemeanors is Allen's sharpest and most profound work, a parable wherein the consequences of postmodern nihilism are pushed to the limit, a lament about the moral darkness into which our society is sinking. But it is also, put simply, a Woody Allen film. So rather than feeling like a heavy-handed sermon, it plays like an absurdist comedy with a philosophical twist. Only Allen could pull that off, and in Crimes it comes off without a hitch, which is to say, brilliantly.

Martin Landau, in an exquisitely controlled performance, plays the role of Nietzchean superman: a wealthy, respected opthamologist who murders his mistress to prevent messy complications in his perfect life. That's the "crimes" part of the title's equation. The mistress - while she's still alive, that is - is played by a strikingly youngish Angelica Huston, who imbues the role with an edgy, intense instability.

Across town, Woody Allen and Allen Alda duel to win the affections of a PBS documentary producer, played by Mia Farrow. Woody Allen plays, well, Woody Allen - but with less whining and more anger, frustration, and intellectualism than his usual nebbish character. He's a struggling documentary filmmaker who would rather make a movie about a philosophy professor than pander to his brother-in-law (Allen Alda). But, in the end, he follows the money and agrees to film Alda's biography for PBS. Alda's character is a flagrant womanizer who rides roughshod on his sitcom production team while spewing cheap truisms like "If it bends, it's funny; if it breaks, it's not funny" and "Comedy equals tragedy plus time." That's the "misdemeanors" part of the movie. Alda is successful; Allen is broke.

Sam Waterston, playing the Jewish rabbi, is the link between this pair of ethical struggles, providing a moral compass while gradually losing his sight.

It all sounds very dark when told this way, but the movie is wickedly funny thanks to Allen's excellent ear for dialogue. When Martin Landau's Mafioso brother, played by Jerry Orbach, comes over to discuss ways of dealing with the jilted mistress (she's threatening to confront Landau's wife), he raises the possibility of murder. "What'll they do?" asks Landau's character in shock. "What'll they'll do? They'll handle it," Orbach says matter-of-factly.

Or when Woody Allen is telling Mia Farrow about how much he hates having to film his brother-in-law's documentary. "But he's an American phenomenon!" she says of Alda's character. "Yeah, well, so is acid rain," Allen replies.

This is funny stuff, situated on the edge between seriousness and farce, while retaining the impact of both. The farce captures the viewer's attention as the movie's action occurs, allowing laughter to cover all bets until the moral dilemmas gradually sink in. And once planted there, they haunt the viewer for days afterward, causing him to think about the existential terror of living in a Godless universe, a place where the only currency for greatness is material success in the here and now.

That existential terror is what makes Woody Allen's nebbish characters tick in all of his films. They're confused as to how to carry themselves in the absence of an absolute morality, yet horrified at how peers invoke relativism as a license for bad behavior. Somehow, it's just not right to have an extramarital affair or be a pompous womanizer or an arrogant intellectual loudmouth. But, where does it say so in the postmodern ethics handbook? If one actually prospers as a self-serving egomaniac while the meek and conscientious perish, then maybe the religions of old got it all wrong; perhaps the Biblical laws only apply to a fantasy place while the real world is governed by a darker Darwinian code. This tension between the theoretical teachings of religion and the empirical observations of the worldly man paralyzes Allen's nebbish characters, causing them to act weak and foolish, sometimes even leading themselves into personal ruin.

It's this last part - the outward actions - of Woody Allen's nebbish personality upon which most people fixate without understanding or appreciating the philosophical nuances of his character. They whine about his whining and bitch about his wimpy hijinks, his inability to be a "real man," and in so doing miss the point entirely. Allen isn't celebrating this kind of behavior in his movies; he's lamenting it, indicting the bleak moral void into which the world has sunk and its deleterious effects on the existentially aware man. In a kinder, earlier time, perhaps his little nebbish would be a saint, but in twentieth century Manhattan, he's just comes off as an impotent anachronism.

In a way, there's righteousness in Allen's on-screen nebbish that is sadly lacking in his real life persona. I suspect Allen knows this and in fact tries to make up for his improprieties by making films that are smarter and more moral than himself. Indeed, one of his cinematic influences is Ingmar Bergman, who once remarked: "I could always live in my art, but not in my life."

In Crimes and Misdemeanors, Allen lives more fully than in any of his other films, redeeming himself so completely with his moral statement that one is persuaded to forgive his latter-day sins in the real world and simply respect him for the fine philosopher he is. So, if I were he, I wouldn't worry about advance generations looking down on my being with scorn. Based on the merit of this film alone, I think Allen's afterlife in the classrooms of the future should be very secure indeed.

posted 6:54 PM | 0 comments

Thursday, March 21, 2002

Reception

I left work early yesterday, at around 4:30, in order to attend a reception downtown for the winners of the Art Walk competition.

These sorts of things make me nervous. How different I am from most people becomes so clearly apparent in such situations that I feel alienated from the gabbing mob and go on the defensive, waiting for someone to spot the weirdo and challenge me to a duel of cool. A squint. A stare. A full up-down scan of my engineer geek-chic.

This was supposed to be a gathering of artists, and I was concerned about not looking like one. This weekend, I was imagining myself donning a fake goatee or soul patch, giving my blond hair that fashionably messy look, and Method acting my way through two hours of conversation, wine, and hors-d’oeuvres. The night before, I had a dream wherein someone pulled off my faux facial hair and the entire room gasped as someone shouted: "Oh my God, he's not an artist - he's an engineer!"

Instead, I came to the event directly from HP wearing a pair of jeans and a dark red linen shirt that had been ironed that morning, but by now more closely resembled a ruffled pirate's shirt. My hair was a dirty blond mop. No gel, no brushing. And, I didn't have the energy to act like anyone except myself.

I arrived early, so I parked in front of the exhibit space and - partly to calm my nerves and partly to actually accomplish something - went for a walk to the Art Shop, located one block over and three blocks down. Man, I miss walking in urban areas. There's so much to look at - buildings, people, construction - and, despite the so-called undesirable human elements, it just feels safe. I need to move back downtown. But, I digress.

I wanted to visit the Art Shop because I needed to examine various mounting materials for presenting my photographs in the exhibit. As strange as it may seem, I've spent more time figuring out how to use the negatives I took last August than the photo shoot itself required. Way more time - perhaps 10 times as much.

I'm beginning to realize that in art, just as in manufacturing, more effort goes into figuring out how to execute a design than in actually drawing one up. They never really teach you that in engineering school: that a lot of the genius in making something lies in fabricating it, not just in how elegant the CAD drawing or photo negative looks. You can calculate ink wetability on a silicon architecture channel or determine the proper exposure of a piece of film using some arcane complex differential equation. But, in the end, you have to build the ink channels up in a FAB somewhere and process your little piece of negative film somehow. These are things that are so complex and open for errors as to make them theoretically intractable problems. Throw out the Navier-Stokes. Empiricism is the only way that works. That's why I think trade secrets are just as important as patents, if not more so in some cases.

A good case study is the Lego brand of building blocks. It's a simple enough concept. The 3D CAD drawing couldn't be simpler, actually. Still, it took the company years to figure out how to manufacture the little bricks so that they would fit together so well. It's harder than it looks and is not a patented process. By the time Lego had a hit on their hands, no competitor could come to market fast enough to prevent Lego from attaining a virtual monopoly of the market. Have you seen the price of Legos? We're not talking commodity prices. Yet, the damn things are nothing more than molded plastic bricks. How much more commodity could you seemingly get?

Anyway, back to my specific task at hand. The quality and availability of various photo presentation materials will influence which of three display options I choose. The first and easiest is to scale up the resolution of the existing Flash movie and project it in a dark room with an LCD projector run off a laptop. Second, is to blow up 6-8 of the choice stills into a 3 by 5 foot format, mount them on foam core, and hang them in what is really the best space in the building - the front lobby. Third, is to frame the 8-by-10 silver halide hand prints in the traditional way and array them on the same wall, gallery-style.

As of this weekend, I had only tested the large-format option. I rather like the result. There's a visceral impact by virtue of its sheer largeness and concomitant ability to draw you into the scene, but the image lacks the depth and detail of true silver halide prints. The 8-by-10 silver halide prints are absolutely gorgeous and, when framed, would appear more arty and professional - but lack that engulfing quality. The Flash essay would totally immerse the viewer in the underground world of mass transit, both visually and aurally, but would not be in as visible a space as the print media (back room versus front lobby).

What to do? I figure I can use a projector at work to tweak the Flash movie this weekend. But, I don't really know much about framing. Ergo, my walk to the Art Shop.

Once there, I found something I liked, bought it, and put it in my car. I went to the reception, which was a painless and quick tour of the exhibit space including a presentation about how to prepare pieces for display with the rail-and-wire suspension system. Everyone else was dressed like me and seemed just as antisocial. I never felt like I belonged in a crowd so much before. On the drive back home, I got to thinking that maybe I do look like an artist because I'm, well, making art. A real artist is someone who defines himself or herself by what they do and not how they merely appear. I mean, I'm not a DKNY-clad SoHo pretender living in a 2-million-dollar Manhattan loft - and maybe that's a good, not bad, thing.

Once home, I played with framing. A gallery photo presentation frame is a nice thing, with a super-white, acid free mat and foam core mounting board held inside a jet black aluminum frame. At about 25 bucks, it's also an expensive thing. But, I'm sure custom framing would be much worse.

I was shocked at how much better a photo looks when properly framed. A gallery display focuses the viewer's attention by surrounding the art with nothingness and placing a boundary around the object, isolating it from the distracting clutter of its greater environs. And the bright white mat and dark black frame serve to calibrate the eye to the full dynamic range of black-and-white photographic intensities. Instead of serving as a wall decoration, each work feels like a little reality capsule, capable of transporting you to another place.

When you calculate the sum total of the developing, printing, and framing time/cost, I have easily exceeded the up-front investment required to get the images down on film in the first place. And, these post-photography steps add just as much value to the final product as the so-called act of artistic creation. Just to verify this, I took a poor photograph and put it in the snazzy frame. Sure enough, it was transformed into an object de art. Similarly, the mounted 3 by 5 photo blowup went from looking like a drab computer printout to functioning as a teleportation window floating on my living room wall.

So what I'm learning is that things post-design matter. There's just as much intellectual property in execution as in design. You can copyright a photo or patent an invention, but that's just where the creative game starts, not where it ends.

posted 12:55 AM | 0 comments

Tuesday, March 19, 2002

Jay and Silent Bob Strike Back: An Exercise in Time Forever Lost

One of my coworkers, Steve Seinfeld, once said to two loud gabbers outside his cubicle: "Here's five dollars. I want the last five minutes of my life back." After sitting through Jay and Silent Bob Strike Back last night, I had much the same reaction, except it's two hours I want back and Mirimax needs to pay me, not the other way around. I kept waiting in good faith for the movie to redeem itself and got nothing in return but a four-dollar rental bill and an overwhelming sense of wasted time as the credits began to roll.

What's so bad about this last installment of Kevin Smith's New Jersey series? Everything. Well, not quite everything. The technical aspects were fine, but in Hollywood, just about every picture has the cinematography, sound, and lighting bases covered as a matter-of-course. As Smith's early, shoestring-budget films attest, it's the creative content that really matters. And in this picture, it registers somewhere between stupid and tasteless.

The film talks the hip postmodern talk, but swaggers so inanely through the parody motions that it seems dumber, not smarter, than its targets. That's a neat trick: to make a parody of, say, Charlie's Angels that's less funny than the original. Must I point out the cardinal rule of satire for Mr. Smith? In order to spoof a subject, you have to present it within a sensibility that is hierarchically above - or at least outside of - the inane logic of the target. Otherwise, the audience won't be able to tell the difference between your mockery and the real thing and accuse you of tasteless homage.

Or, perhaps a mere definition of satire, lifted from Webster's Collegiate, will suffice: "A work in which vices, follies, stupidities, abuses, etc. are held up to ridicule and contempt." In Jay and Silent Bob Strike Back, nothing is held up to anything remotely resembling examination, that is, unless you count several private body parts. Rather, the whole affair sinks below the level of its basest pop cultural references.

So we watch, for an hour-and-a-half, two utterly stupid characters colliding with countless other stupid characters, going on a stupid journey, doing stupid things, and alluding to stupid shows or movies. All this without any overarching, wry sensibility to tie it all together. This film isn't Dumb and Dumber, it's Stupid, Stupid, Stupid, Stupid, and Stupider. In fact, this film joins Darron Aronovsky's Pi as one of the few titles that is best expressed in mathematical, rather than English, terminology. Sadly, HTML does not support the character set required to express an infinite geometric sum of 'stupid' terms, or I could neatly re-name it in these pages. I shall leave the derivation of the series ratio as an exercise for the reader.

Jay and Silent Bob Strike Back is all the more disappointing having come from the hands of a writer-director whose previous output included the excellent Clerks and Chasing Amy, films amazingly produced on budgets of $27,000 and $200,000, respectively. But whenever Smith goes big-time, things just seem to fall apart. His gritty bathroom humor is out of place amid the studio system gloss, a shtick that plays better within the context of independent production values. And perhaps more fundamentally, I suspect that after four Jersey films, Smith has run out of stories to tell and things to say.

Allegedly, that's what Smith originally thought after Dogma, but he was somehow persuaded to go one more with an ode to his two simpleton characters, Jay and Silent Bob. And there's actually nothing wrong with the idea. In fact, from much the same template (although with admittedly more regal starting material - Shakespeare's Hamlet), Tom Stoppard managed to draw up the brilliant Rosencranz and Guildenstern Are Dead. But in order to re-frame your material around a pair of imbeciles, you must follow the rules of satire. Stoppard clearly knows this; Smith apparently doesn't.

Not that Kevin Smith is a lost cause, but maybe it's time for him to go to film school, or just take some time and read a few books in order to get a grip on the more advanced elements of narrative. He was already on the right track with Clerks and Chasing Amy, but as Jay and Silent Bob shows, the boy's in a rut and needs to grow as an artist. Given the financial success of his last two films, he can certainly afford to take time off to improve his craft. At the very least, the reduction of viewers' wasted time yielded by such an investment would be advisable on legal grounds alone.

posted 6:25 PM | 0 comments

Sunday, March 17, 2002

Rainy Day Man

The last few days have been dark and blustery - a nice change of pace from San Diego's typical Bright! Bright! Sunny! Sunny! climate. As I write this, a gentle rain pelts down on my patio, providing a soothing background for this journey entry. I just came in from the cold and damp, back from dinner at Hunan, and am now going to warm my toes by the crackling Blog. Just let me take my socks off ...

Against all conventional wisdom, rain never fails to lift my spirits. To an indoors person whose idea of a good time is curling up on the sofa and reading a long tome - blanket on my lap and pot of tea at my side - inclement weather is a godsend. It provides an excuse larger than youself for staying in when everyone else wants to go out. It adds a dimension of coziness to your home, providing real physical boundaries between you and elements. And it provides a Zen focal point appropriate for just staring out a window, cleansing all those warring free radical thoughts from your mind.

No one believes me when I tell them I miss the rain of Texas and Minnesota. But I do miss it: the intense spring showers, the summer thunderheads, the autumnal bluster. The long nights filled with homework, Cosmic Encounter, Facts in Five, movies and endless pots of jasmine or earl grey tea. Bowls of Martha's vegetarian chilli. Quiet crossword marathons. These scenes were often accompanied by falling precipitation that, continuing into the night, would hypnotically wean me from my bedside novel into a deep, peaceful sleep.

They magic of rain doesn't end when the drops stop falling, either. After a shower, the streets and sidewalks dazzle: the most mundane intersection takes on surreal proportions, the haloes of light looming large, a warped mirror at your feet. You breathe in the mist, smell the fresh air, and somehow feel a heightened sense of being. And if you're me, you think back to Gene Kelley's solo scene in Singin' in the Rain and begin mouthing lyrics quietly to yourself as your shoes splish and splash in the odd sidewalk puddles.

Speaking of which ... looking out my window now, I see the rain has subsided to a fine mist. It's my cue to end this ode to rain and step outside to enjoy it. Sadly, you Bloglerites aren't here to share the experience. But be assured that as your proxy, I'll sing a little song for you as I kick down the cobblestones.

posted 9:46 PM | 0 comments

Friday, March 15, 2002

From the archives

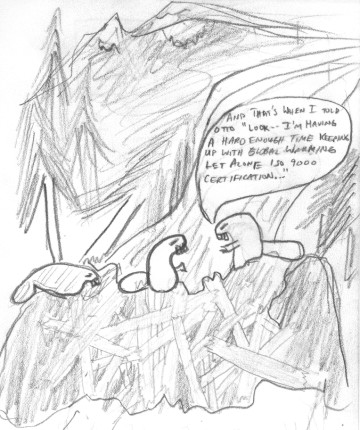

It was 8 AM around November 1998. I was sitting in my Intermediate Fluid Mechanics class in Amundson Hall, University of Minnesota ... and the last thing on my mind was the growing bubble problem. Instead, I was busy sketching this:

posted 12:17 AM | 0 comments

Monday, March 11, 2002

Life Instructions for Monday, 3/11/02

Wake up at 9. Shower. Shave. Eat a granola bar. Drive to work. Dispense coffee. Pour milk. Drink coffee at desk. Sit at desk for an hour. Read blogs, look at news, whatever. When awake, wander around and talk to people. Go to testbed. Try to figure out why there are metal shavings all around it. Realize main gear has been sawed off. Motor replaced with stepper motor. Nice, but now it doesn't work. Go back to desk. Plug in Jornada. Does not update. Not connected. Re-install Microsoft ActiveSync. Success! Look at clock. Noon. Time for lunch. Think of eating at taco shop. Think about Josh's Taco Stupid idea. Grin and laugh foolishly. Look at bank account. Realize not enough funds to start franchise. Shrug. Whatever. Thought occurs that 'whatever' is today's operative word. Whatever.

Return from lunch. Think about downloading porn. Do not download porn to prevent from getting fired. Work on testbed some more. Do some Excel and Powerpoint. Talk some more. Make some calls; send out email. Make some tea. Go home. Put on blues LP. Make dinner. Do the New York Times crossword (omit this step if Thursday or Friday). Dial in. Blog. Email. Make tea (or get coffee with friends). Read Atlantic, New Yorker, Harpers (if anything appears interesting). Go for a walk. Read at Borders. Walk home. Have a snack. Brush teeth. Read book. Go to bed.

Rinse thoroughly with ironic introspection and repeat with modifications ad nauseum until retirement, death, moment of clarity, or financial windfall. Not to be used by persons with authentic life force. If feeling of malaise persists, think of silly pop cultural things, like Barney being slow roasted on a rotating barbeque spit or the Pilsbury doughboy baking into a crispy cookie. Mmmm. Cookies.

posted 11:58 AM | 0 comments